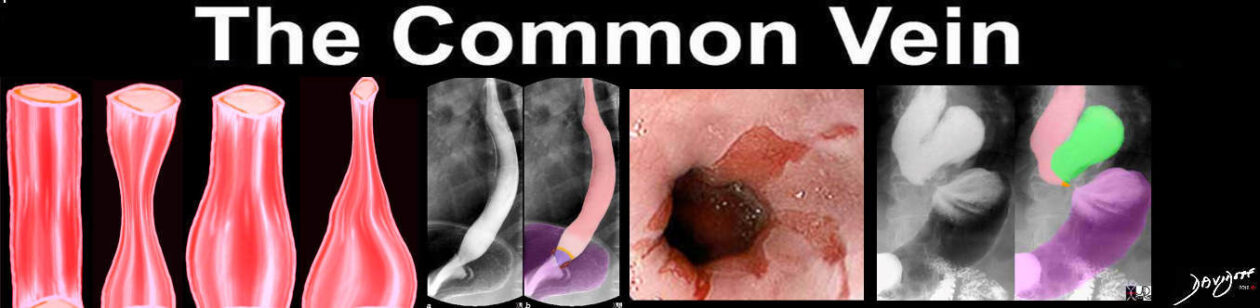

The tube-like structure of the esophagus is key to its proper function as a conduit from the mouth to the rest of the digestive system. In essence, the esophagus is simply a long tube. However, it is more complex than that with several distinct regions each of which has different properties and functions. The segments differ from being tight muscular sphincters at either end of the tube that allow one way flow, preventing reflux, to segments that have varying contraction and relaxation peristaltic properties.

Found Between Two Sphincters

The esophagus lies between two sphincters. The upper esophageal sphincter enables food to enter the esophagus while the lower esophageal sphincter (LES) prevents reflux of gastric contents.

key words esophagus normal motility contraction wave peristalsis primary stripping wave physiology function receptive relaxation upper esophageal sphincter lower esophageal sphincter LES UES esophageal body pharynx

Ashley Davidoff MD TheCommonVein.net 73368b06.800

Structural Characteristics

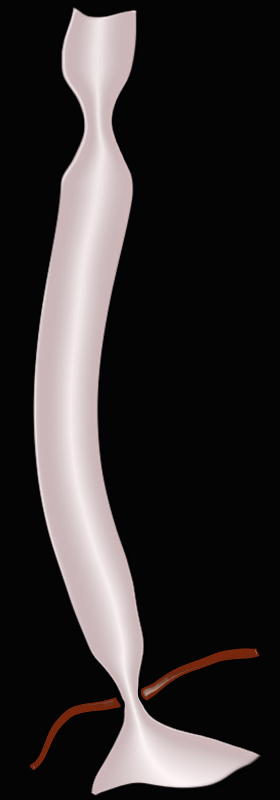

The esophagus is a hollow tube that lies in the posterior mediastinum and is an important component of the gastrointestinal tract. It courses behind the trachea and left mainstem bronchus and in front of the aorta. The actual length varies but ranges between 18-26cm. It is important to note that the length changes slightly with each swallow.

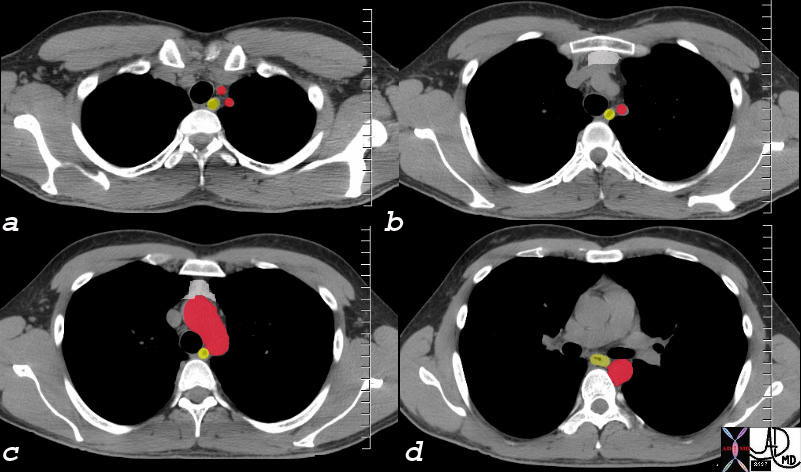

The CT scan of the upper chest shows the esophagus (yellow) at the thoracic inlet (a) leftward of the trachea (black) and medial to the left subclavian artery (a and b). Lower down the trachea remains medial while the aortic arch becomes an anterior and lateral relation.(c) Below the carina, (d) the left main stem bronchus is an anterior and leftward relation while the descending aorta lies lateral.

key words: esophagus relations left subclavian artery trachea aortic arch ;left main stem bronchus normal thymus 30 year old normal anatomy CTscan C

Ashley Davidoff MD TheCommonVein.net 73610c02

The wall of the esophagus is comprised of four distinct structural layers: It is important to note the lack of a serosal lining. In the rest of the gastrointestinal tract an outer lining exists throughout and is called either a serosa or an adventitia. This is an important fact since disease such as malignancy in the esophagus has little resistance to prevent it from spreading through the wall.

The mucosa is comprised of a nonkeratinized stratified squamous epithelium. This acts as a permeability barrier and contains the regenerative capacity of the esophagus.

Just below the mucosa is the submucosa. Within this layer one finds connective tissue, blood vessels, lymphatic structures, as well as neurons. Acini, or clumps of cuboidal cells are also present in this layer and these provide various substances such as mucus, bicarbonate, and growth factors that are key in maintain the proper function and structure of the esophagus.

The muscularis propria is the next layer is comprised of 2 layers of muscle: the innermost circular layer and the outer longitudinal layer. The esophagus is the most muscular portion of the gastrointestinal tract.

The esophagus begins at the upper esophageal sphincter (UES) where the cricopharyngeus and inferior pharyngeal constrictor muscles meet. This is at about the level C6, 15 cm from the central incisors.

The UES is critical in preventing patients from swallowing air as it remains in the contracted or high pressure position when the patient isn’t swallowing. Upon initiation of a swallow, the UES relaxes (see below) and allows the bolus to enter the esophagus. From there, the musculature propels the bolus towards the stomach.

The upper 5-33% of the esophageal muscle is of the skeletal type while the distal 33% is smooth muscle. The region in between is a mixture of both skeletal and smooth muscle.

At the distal end of the esophagus is another important sphincter known as the lower esophageal sphincter (LES). The main function of this sphincter is to prevent the reflux of gastric contents back into the esophagus. The distal esophagus terminates about and it terminates 3-5 cm below the diaphragm.

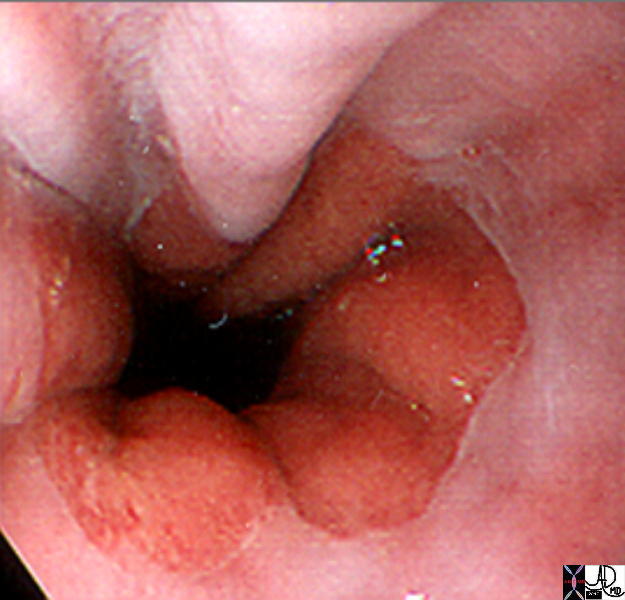

The gastroesophageal junction (aka Z line, ZZ line or squamocolumnar junction) is clearly outlined as the squamous epithelium (white) transitions to the gastric epithelium (reddish pink mucosa)

Ashley Davidoff MD TheCommonVein.net 73474

The transition from esophageal to gastric mucosa, easily recognizable by a color and texture change, takes place along an irregular dentate or zigzag line, known as the “ZZ” line or the “Z” line.

Applied Biology

With the unique structural and neurologic anatomy, many conditions can cause dysfunction of the esophagus. Anatomic alterations with rings or webs, muscular dysfunction, or neurologic conditions, both localized and systemic, all can wreak havoc on the esophageal function. Reflux esophagitis due to malfunction of the LES function is a common disorder which allows acid from the stomach to reflux into the esophagus. Severe inflammation associated with severe pain may result. Scleroderma, a connective tissue disease, affects the smooth muscle and hence distal esophageal function.